Another horsemeat scandal is just waiting to happen. Recent research by consumer organisation Which? revealed that the number of official tests on food fraud in the U.K. dropped by 16.8 percent between March 2012 and March 2013. Some local authorities, the organizations responsible for checking that food is what it is claimed to be, didn’t carry out any tests at all.

“We expect to be sold food that is safe to eat and is what it says it is,” said a Which? spokesman. “So many of us were shocked when last year it was revealed that horsemeat had found its way into many foods sold in our supermarkets.

“But the latest Which? investigation suggests that this is not so surprising as in some areas of the UK no testing is being carried out to check for food fraud. Some local authorities are also struggling to ensure businesses comply with hygiene rules.”

Which? used data collected by the Food Standards Agency from local authorities throughout the U.K. in its investigation. These data showed that overall food testing fell by 6.8 percent from the previous year, continuing a decline, and testing for labeling and presentation fell by 16.2 percent. No official hygiene sampling was carried out at all by six local authorities.

The number of food standards interventions dropped even further, down by 16.8 percent allowing the potential for further food fraud to go undiscovered.

“No one wants another horsemeat fiasco, so it is very worrying that local authority food checks are in decline. We want to see a more strategic approach to food law enforcement that makes the best use of limited resources and responds effectively to the huge challenges facing the food supply chain,” said Richard Lloyd, Which? executive director.

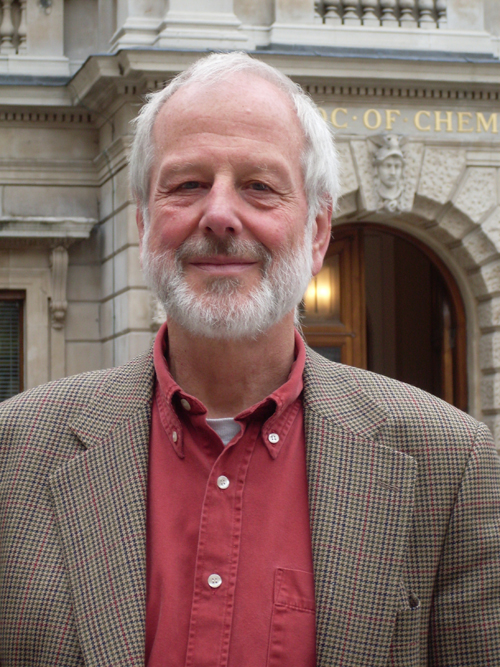

And it is the food supply chain which is causing particular concern after the horsemeat scandal. A recent U.K. government report by Professor Chris Elliot, director of the Institute for Global Food Security at Queen’s University Belfast, states that the emphasis on providing cheap food — he quoted an example of a food manufacturer being asked to produce a beef burger costing just GBP 0.30 (USD 0.49, EUR 0.36) — has led to complex supply chains which are ripe for fraudulent activity. In fact there has been some comment that it is not so much a food chain nowadays, but a tangled worldwide food web. “And that makes it open to abuse.”

“I believe criminal networks have begun to see the potential for huge profits and low risks in this area. A food supply system which is much more difficult for criminals to operate in is urgently required,” said Elliott.

When Elliott said that the meat industry is particularly vulnerable to the buying and selling of meat by traders and brokers, he could just as well have substituted the word “fish” for “meat.”

“Traders and brokers will buy and sell meat of any quality or quantity. Most traders don’t have physical possession of the meat they deal in,” said Elliott. “They trade from an office, even over a mobile [cell] phone, while the meat will more than likely be held in a cold-store.

“They may never own the meat, but merely arrange the deal and for the most part their main concern will be price rather than the actual quality of the meat itself.”

Horsemeat sells for less than half the price of beef, so for an unscrupulous trader there is temptation to mix the two meats together. Once they are minced or cubed and then frozen into blocks, only DNA tests can spot the equine origin.

“The ever increasing pressures to reduce costs can cause careless procurement practices and allows this material to enter the UK food system,” said Elliott. “Some of this meat may well not be fit for human consumption.”

Under these circumstances, it is surely not the time for official enforcement agencies in the U.K. to be relaxing their vigilance.