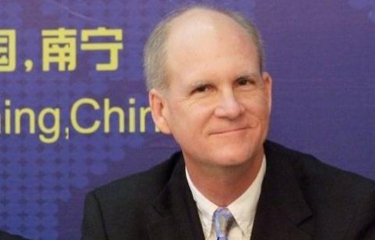

The government of Myanmar has targeted aquaculture as a solution to widespread malnutrition and rural poverty in the Southeast Asian nation. With its 2,000 kilometers of coastline, Myanmar has the potential to reach the production levels of its neighbor, Thailand, as a seafood producer, according to Kevin Fitzsimmons, a professor in the department of soil, water, and environmental science at the University of Arizona and director of the department’s international programs.

The country has begun to market its seafood exports, including appearances at the annual Seafood Expo Global in Brussels, Belgium. And a new program, the Myanmar Sustainable Aquaculture Program (MYSAP), which was given EUR 25 million (USD 27.6 million) in funding by the European Union and German development agency GIZ, is specifically aiding in the country’s development of its aquaculture sector.

Fitzsimmons has taken a two-year leave of absence to work on MYSAP. Fitzsimmons, who previously worked on a USAID supported project from 2015 to 2017 to develop sustainable aquaculture in Myanmar, talked to Seafoodsource about the potential of Myanmar’s aquaculture sector and the environmental and investment challenges the country faces in its aquaculture-related efforts.

SeafoodSource: Is there sufficient investment in Myanmar to realize the kind of aquaculture developments needed to satisfy demand and nutrition requirements as envisioned in the MYSAP project outline?

Fitzsimmons: The project is able to make some investment, but the vast majority of investment is coming from domestic Myanmar funds. The demand for seafood is met at a basic level, but interest in fishes other than carps is great. Most of the new production is focused on these other species.

SeafoodSource: What are the species drawing the most interest in Myanmar?

Fitzsimmons: Species diversification is a major topic. Tilapia, Asian sea bass, barramundi, and pangasius have been leading the way. But endemic species including butterfish, snakehead, climbing perch, Anguilla eel, and swamp eel are also receiving a lot of interest.

SeafoodSource: How much potential does Myanmar have to become a significant exporter of seafood?

Fitzsimmons: Myanmar has great potential to be a major exporter. Domestic demand is largely met. With a coastline roughly equivalent to Thailand and Vietnam and similar freshwater resources to those countries, Myanmar should eventually be an exporter on a similar scale.

SeafoodSource: Is more international investment and partnership needed?

Fitzsimmons: International investment is especially needed on the vendor or supplier side. New feed mills, equipment suppliers, and harvesting and processing equipment are all in great demand. Local partners can be found for some aspects, but the bulk of funds and technology will need to come from outside Myanmar.

SeafoodSource: How can Myanmar source sustainable levels of feed locally to meet the kind of growth it predicts for its aquaculture sector?

Fitzsimmons: Several of the key ingredients will need to be sourced abroad. Bulk handling equipment at the Thilawa Port will come on-line soon and facilitate bulk delivery of soybean and various grains and oils. Myanmar also has great agricultural resources growing their own wheat, rice, beans, and several pulses.

SeafoodSource: China has some big players in aquafeed production that have recently built plants in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ecuador, and other countries with growing aquaculture sectors. Are these companies looking to build their presence in Myanmar?

Fitzsimmons: I have attended some of the meetings between “big players” from China and Myanmar operators, but so far I am not aware that any of the big Chinese players have made any investments.

SeafoodSource: To what extent is Myanmar’s aquaculture production model being geared as a satellite production base for Chinese demand?

Fitzsimmons: China is the number-one market for Myanmar seafood products, followed by Thailand. Huge amounts of crab and crab products, shrimp, eels, and pangasius are exported to China, both wild-caught and farmed.

SeafoodSource: Does that trade involve Myanmar-owned entities supplying China-based buyers or are Chinese operations in Myanmar behind the production?

Fitzsimmons: There are relatively few, if any, investments of Chinese-owned and -operated farms. What is much more common are for Burmese-Chinese families to make the investment and then sell to Chinese buyers. There may be some quiet investment from China and China-Taiwan.

SeafoodSource: Are the regulatory and training capacities of the Myanmar government adequate to facilitate the kind of modernization and expansion of aquaculture you envision?

Fitzsimmons: The Department of Fisheries inside the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation has been severely underfunded for many years. We have been working closely with the Department of Fisheries to facilitate modernization and build capacity. Several other national and international organizations - the FAO, Danida, AusAid, NorAd, USAID, and others – are also working to build capacity in this critical agency.

SeafoodSource: What kind of progress is Myanmar making in terms of reintroducing polyculture and restoring mangrove forests, two of the goals stated in the [published by GIZ] project plan?

Fitzsimmons: The progress instituting polyculture and mangrove restoration has been slower than expected. One of the favorite sayings of Burmese is that “seeing is believing.” Thus, we are relying on demonstration farms and partner farmers to conduct farm-based trials so that neighbors can observe and make their own conclusions.

SeafoodSource: How likely is it that Myanmar can restore its wild stocks given the serious depletion that has occurred there? Reports have shown that some stocks are at 10 percent of their 1970s levels.

Fitzsimmons: It will be nearly impossible to restore wild stocks in the short-term due to severe overfishing. Our vision is to provide domesticated stocks for most of the most popular seafoods.

SeafoodSource: What was the key message you brought to the recent conference on feed you appeared at in Zhengzhou, China?

Fitzsimmons: Our primary message was that the revolution in alternative proteins and oils for use in aquafeeds is just beginning. The explosion in insect-based ingredients, single-cell bacteria, fungi and algae, fermented products, and plant and animal processing co-products are flooding onto the market at competitive pricing.

SeafoodSource: What were some of the key learnings you took from the conference in terms of progress in China on alternative feed ingredients?

Fitzsimmons: We were very impressed with the scope and high level of technology that the Chinese scientists were applying to these issues in China. The entrepreneurial know-how, ease of starting businesses, and opening of markets are not at the level of Silicon Valley, but they are improving all the time.

Photo courtesy of the University of Arizona Institute for Energy Solutions