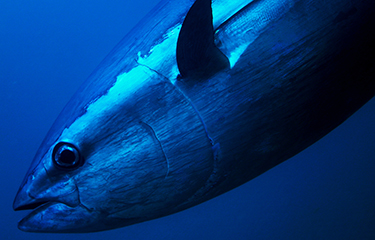

A move initiated by the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump to roll back rules protecting Atlantic bluefin tuna could be resulting in a decline in the population of the species.

In April 2020, NOAA Fisheries introduced changes to the management of the Atlantic pelagic longline fishery, with the goal of increasing swordfish catches. U.S. fishermen only caught 34 percent of the quota for North Atlantic swordfish in 2018, according to a NOAA press release.

“For seafood lovers in the United States, this means fewer opportunities to purchase local, sustainably harvested swordfish products,” the agency said.

The changes include opening three new areas for pelagic longline fishing – off New Jersey, North Carolina, and in the Gulf of Mexico – previously closed during the January-to-June bluefin spawning season, though fishermen must still use weak hooks when bluefin in that time period.

“Providing access to these areas relieves an unnecessary regulatory burden on pelagic longline fishermen. It gives them greater flexibility for where they can target swordfish and yellowfin tuna throughout the year. They will also be able to use their expertise to avoid interactions with bluefin tuna,” NOAA Fisheries said. “In addition, these changes will allow NOAA Fisheries to collect more data. This data is used to evaluate management decisions, set retention limits, close fisheries, and assess stocks.”

All previous bluefin-related restrictions will be removed from the Cape Hatteras Gear Restricted Area, while the Northeast U.S. Closed Area and the Spring Gulf of Mexico Gear Restricted Area will be monitored on a three-year basis to ensure bluefin tuna landings and dead discards stay below the threshold permitted by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), which sets an annual quota for all countries engaged in Atlantic bluefin fishing. If fishermen in the monitored rea exceed 55 percent of the quota, April and May access will be rescinded, and if they exceed 72 percent of the quota, access to the areas may be revoked.

“In both the Gulf and Northeast areas, staying below the threshold would suggest that these closed areas are not needed to protect bluefin from overfishing. It would show that other management measures are successfully ensuring that bluefin tuna catches stay within the overall science-based quota set by ICCAT,” NOAA said. “At the end of the three-year evaluation, NOAA Fisheries will analyze the information we collect. We will then determine whether we will continue to use these closed areas to manage bluefin tuna bycatch.”

In its release, NOAA said continued below-quota harvesting of its swordfish quota in the United States could lead to “ripple effects for the future conservation of stocks.”

“A portion of our quota could be reassigned to another country if we consistently do not use it. And the receiving country could have less robust domestic management for reducing bycatch or ensuring the survival of released fish,” the agency said.

However, ICCAT has reported that while Atlantic bluefin stocks are up from previous levels that resulted in a push to list the species as endangered, the population stands at just 13 percent of its levels if it were not targeted for fishing at all. And it has said that if the current quota of 2,350 metric tons of bluefin is maintained, there is a 94 percent likelihood that Atlantic bluefin stocks will be overfished in 2021. A 50 percent cut to the planned quota is necessary in order to eliminate any harm of overfishing the population to allow it to recover, according to ICCAT.

In April 2020, two environmental organizations sued NOAA to prevent the rollbacks on bluefin fishing restrictions, and that lawsuit is still pending.

According to Grantly Galland, a marine biologist with The Pew Charitable Trusts, the restrictions – put in place by the Obama administration – resulted in some signs of recovery for the Atlantic bluefin, which could be at risk with the move by NOAA.

“We had early signals of recovery but raising the fishing quota and now getting rid of the protections in the Gulf of Mexico means the western population of bluefin is under threat again, Galland told NoLa.com.