A new study published in the journal Science reveals that the world’s marine fisheries form a single global network – linked by transnational flows of fish larvae – rather than existing as discrete groups.

Researchers from the United States and the United Kingdom believe that their work could lead to greater international cooperation in the way fish stocks are managed in the future.

The study combined data from satellites, ocean buoys, field observations, and marine catch records to build a computer model of how the eggs and larvae of more than 700 of the world’s commercially harvested fish species are dispersed. The results showed that more than USD 10 billion (EUR 8.9 billion) worth of fish is caught each year in a country other than the one in which it spawned.

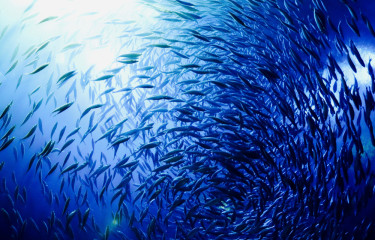

Fisheries are traditionally managed within EEZs, where around 90 percent of the world’s fish are caught. And while adult pelagic stocks can be tracked across international borders, as they tend to swim in large schools, the wider movements of non-pelagic populations are more of a grey area.

Numerous studies have shown that eggs and larvae drift on ocean currents and that plankton communities are connected, but this is the first time that experts in oceanography, fish biology, and economics have collaborated to examine the global nature of this complex area, and been able to construct a network showing the larval flows between nations.

“Data from a wide range of scientific fields needed to come together to make this study possible,” said lead author Nandini Ramesh, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at the University of California, Berkeley.

“We needed to look at patterns of fish spawning, the life cycles of different species, ocean currents, and how these vary with the seasons in order to begin to understand this system.”

Hotspots of risk for catch, employment, and food security were identified, along with areas of regional interdependence. The most vulnerable nations were identified in the Caribbean, West Africa, Northern Europe, and Oceania. Risks to national GDP and labor force were found to be highest in the tropics, and surprisingly, food security risk was also identified in some European nations. The results strongly point to a need for multilateral cooperation to ensure sustainable management of shared resources

Researchers found, for example, that those nations which are reliant on neighboring EEZs for recruitment of larvae into the general fish population were at risk of losing part of their catch if those fisheries were poorly managed. Habitat destruction, overfishing, and environmental change within an EEZ can have impacts far beyond the given boundaries, and targeted efforts to manage fisheries within an EEZ can benefit many nations.

“Our mapping of how the world's fisheries are interconnected, shows where international cooperation is needed most urgently to conserve a natural resource that hundreds of millions of people rely on,” said co-author Kimberly Oremus, assistant professor at the University of Delaware School of Marine Science and Policy.

Current direction and speed are key factors in the distribution of fish larvae and the research team discovered that although the strongest movements are typically between adjacent EEZs, connections can also extend over longer distances.

For example, the influence of the Guinea Current on the connectivity of West Africa’s fisheries is seen in the large number of EEZs that act as sources to their eastward neighbors, especially between Guinea-Bissau and Nigeria.

In the Baltic Sea, which has weak currents, the largest outward larvae flows come from countries with the longest coastlines – Sweden and Norway.

In the Caribbean, where the north Brazil current flows north-westward along the South American coast, many of the EEZs through which it passes act as sources of fish larvae for the Lesser Antilles.

In the Western Pacific, the EEZs are very large, and most connections here are between immediate neighbors.

In effect, the system of larval distribution was found to display typical scale-free, small-world network properties, where any point in a global network can be reached in a small number of steps. This is the same phenomenon in which strangers are linked by six degrees of separation.

Such properties also bring a risk that threats or catastrophes in one part of the world could result in a cascade of stresses that affect one region after another.

“We are all dependent on the oceans, and when fisheries are mismanaged or breeding grounds are not protected, it could affect food security half a world away,” said co-author James Rising, assistant professorial research fellow at the Grantham Research Institute in the London School of Economics.

“We have made an important first step and hope that this study will be a stepping stone for policy makers to study their own regions more closely to determine their interdependencies,” said Ramesh.