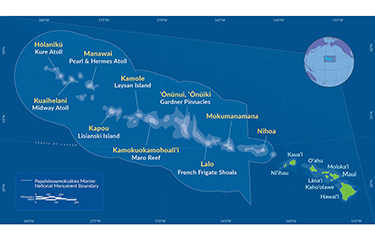

A new analysis by the University of Washington's Sustainable Fisheries Lab is countering a study that claims the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, the largest marine protected area (MPA) in the U.S., caused a “spillover effect” in yellowfin tuna.

The study, “Spillover benefits from the world’s largest fully protected MPA,” claimed it found “clear evidence” of spillover effects for both bigeye and yellowfin tuna. A spillover effect refers to when the population of a particular species in an MPA becomes so abundant that it “spills over” into surrounding areas that can be targeted by fishermen.

The study claimed that there was a 60 percent increase in the yellowfin CPUE (catch per hook) over 3.5 years due to the creation of the MPA. But according to the new analysis, the MPA’s creation coincided with a surge in yellowfin tuna populations across the Western Pacific, and the habitat closer to the MPA was already a better location for the fish – the CPUE was “substantially higher in proximity to the MPA” compared to other location.

The data in the MPA report was problematic, according to University of Washington Professor of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences Ray Hilborn Ray Hilborn.

“The first time we read it, we knew something was off – a 60 percent increase in yellowfin CPUE due to the MPA in just 3.5 years is just too good to be true. But it took a while to figure out exactly how they had reached their outlandish conclusions,” Hilborn wrote. “Our eureka moment was when we realized they had calculated the change in CPUE using absolute values instead of relative or proportional ones. This is a highly misleading way to do it.”

Hilborn's analysis said the catch-per-hook rates should have been proportional across the fishery. The paper also did not take into account the effects of El Niño, an event “that is likely responsible for the major change in yellowfin abundance,” he said.

“In the real world, we expect fish populations to increase proportionally to what the local habitat allows. If the near area doubles from 1 to 2, we expect the far area to double from 0.33 to 0.66,” the analysis states. “By modeling in absolutes, [the paper] distorts the data in favor of areas close to the MPA where CPUE was already high and habitat was historically better. The increase in tuna in specific locations reflects an increase in proportion to its habitat quality.”

Prior to the MPA closure, the area also had relatively little yellowfin catch – "about 1,200 fish per year," according to the analysis.

Hilborn said his lab asked the staff of the Western Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Council to rerun the calculations – which had to be done by council staff as the observer data the original study used is confidential. The second round of calculations found “no evidence for spillover.”

Hilborn's review aligns with his position that MPAs aren’t the answer to ocean biodiversity and sustainability efforts.

Various academic studies have offered conflicting stances on whether the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument has resulted in a change in catch totals. Some studies have found MPAs have either no effect or a positive effect on catch totals, while others found some fishermen were impacted more negatively than others.

The Sustainable Fisheries UW analysis found catch totals may not be effected by MPAs – but fishing effort is.

“The implementation of MPAs frequently results in the displacement of fishing pressure rather than its reduction. Fishermen compensate for lost catch by intensifying their fishing activities outside of the MPA, particularly in the case of mobile fish like tuna that frequently move in and out of the MPA,” the analysis said. “While MPAs can effectively protect marine life inside their boundaries if adequately enforced, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that they are effective at increasing large-scale populations outside of MPA boundaries.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia