A new study prepared for Oceana has found the global blue shark fishery is worth more in ex-vessel value than any of the three major bluefin tuna fisheries – despite having next-to-no management for the species.

The study, organized by Oceana and performed by Poseidon Aquatic Research Management in association with China Ocean Institute, Diatom Consulting, and the University of Santiago de Campostela, investigated the volume and values of the global blue shark fishery. What research found is that the fishery is worth as much as USD 411 million (EUR 387 million) and has evolved from bycatch into a fishery in its own right.

That value makes it worth more than the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery, worth USD 360 million (EUR 339 million) in 2019.

According to the research, blue sharks make up 60 percent of the global shark catch, 36 percent of all traded shark meat, and 41 percent of all traded shark fins. In volume terms, the study estimates nearly 190,000 metric tons (MT) of blue shark were caught in 2019.

Despite the volume and the value of the blue shark fishery globally, currently the of four main regional fishery management organizations – the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), and the Western Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) – only ICCAT has any quota or restrictions on blue shark catch.

“Aside from that one RFMO, management measures don’t exist,” Oceana Research Associate Jillian Acker told SeafoodSource. “We have these fleets that are catching these blue sharks under the same jurisdiction of tuna but don’t have the same oversight.”

The research found the majority of blue shark was caught by distant-water fishing fleets – 74 percent of all blue shark catch was sourced by distant-water fleets, with just 26 percent caught by coastal fleets. Large-scale fleets also dominated, with 90 percent of blue shark catch coming from large-scale longliner fleets.

Of the countries participating in the blue shark fishery, five caught more than 75 percent of the volume: Portugal, Indonesia, Japan, Spain, and Taiwan. Of those, Portugal caught 6 percent, Indonesia 8 percent, Japan 14 percent, Spain 25 percent, and Taiwan 25 percent – with the remaining 21 percent caught by other countries.

Prior thinking, Acker said, was that blue shark is primarily a bycatch species caught during targeted tuna fishing. But the research showed the species has become a targeted fishery to meet growing demand, and in certain instances, tuna has now become bycatch.

“It’s time to rethink the fact that blue shark is just incidental catch in tuna fisheries,” Acker said. “There is a targeted blue shark fishery, and it should be referred to as that.”

One of the main markets for blue shark products is Brazil, where 45,000 MT of the species was consumed either via direct consumption or other uses like pet food in 2017. The species is often used in a popular dish, cação, where consumers may not even realize that they’re eating shark. In fact, most reported never eating shark – even if they’ve eaten cação, Acker said.

Despite the fishery’s high value globally, due to a lack of management, traceability is low and research on its sustainability is minimal.

“Putting a number on how much blue shark is caught each year isn’t something that has been done,” Acker said.

The Oceana study, Acker said, was in part to determine what impacts global fisheries are having on shark species in general, and the organization picked blue shark due to its resilience. Blue shark is a highly migratory species that is highly abundant in global waters.

“If we can’t manage blue shark, which is so resilient, so abundant, how can we expect to manage other species that are more vulnerable?” Acker said.

Now, Oceana is planning to use the results of the new study to advocate for more oversight over the fishery.

"Our plan is to keep up the momentum and bring this research to RFMO meetings in the new year, calling for direct, science-based management measures, such as catch limits and quotas,” Acker said.

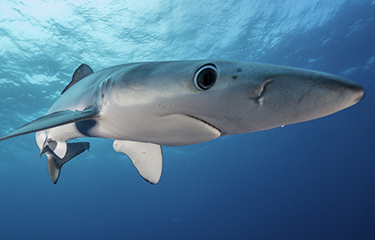

Photo courtesy of wildestanimal/Shutterstock